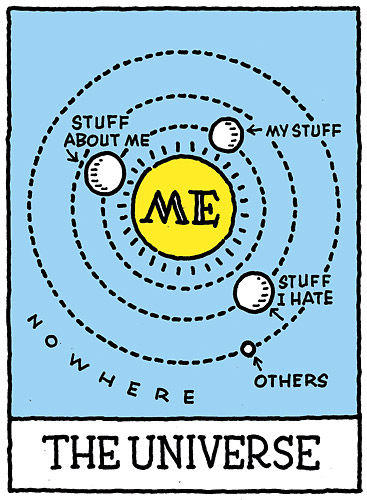

David Elkind’s theory of “Adolescent-Egocentrism”:

In order to gain a proper understanding of the causes behind the teenagers’ deviant and, sometimes, erratic behaviour, it is necessary for us to familiarize ourselves with the various theories that seek to explain adolescence and the primary changes that it results in.

David Elkind, an American Psychologist, devised the theory of Adolescent-Egocentrism (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 38). According to this theory, the period of adolescence is characterized by an “immaturity of the thinking process” (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 38), which he has attributed to “underdeveloped reasoning abilities” (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 38).

As the name of this theory suggests, the key feature of the adolescent period is “egocentrism” (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 38), which has been described as the “heightened self-awareness and self-consciousness” (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 38). As a result of this, adolescents tend to believe that others, especially individuals of their age-group, evaluate their behavior. The others, who are thought to evaluate the individual’s behaviour, are known as the “imaginary audience”, and, in reality, they are not actually concerned with the individual’s behaviour to the extent that he/she believes they are.

“Personal Fable”, on the other hand, refers to the common tendency, among adolescents, to view themselves as unique, different, and invulnerable. It is also accepted that risky behaviours can be linked to Personal Fable, which promotes the notion that one is invulnerable and unique from others; hence, adolescents tend to believe that the consequences of pursuing risky behaviours would not as negative for them as it would have been had someone else done them.

Ego-centrism, itself, emerges due to the gradual development of Piagetian Cognitive development (Vartanian, 2000, p.639). Young children, for example, do not experience adolescent egocentrism, because they lack the ability to think in abstract terms, which theorists believe is a part of formal operational thought (Vartanian, 2000, p.639).

At the same time, it is necessary to understand that adolescents’ formal operational thought are not completely developed, and, as a result, adolescents fail to realize the similarity between their own experiences and those of their peers, and tend to view themselves as unique (Vartanian, 2000, p.639).

Allison Davis’ “Socialized Anxiety” theory, and its role in Adolescent behaviour:

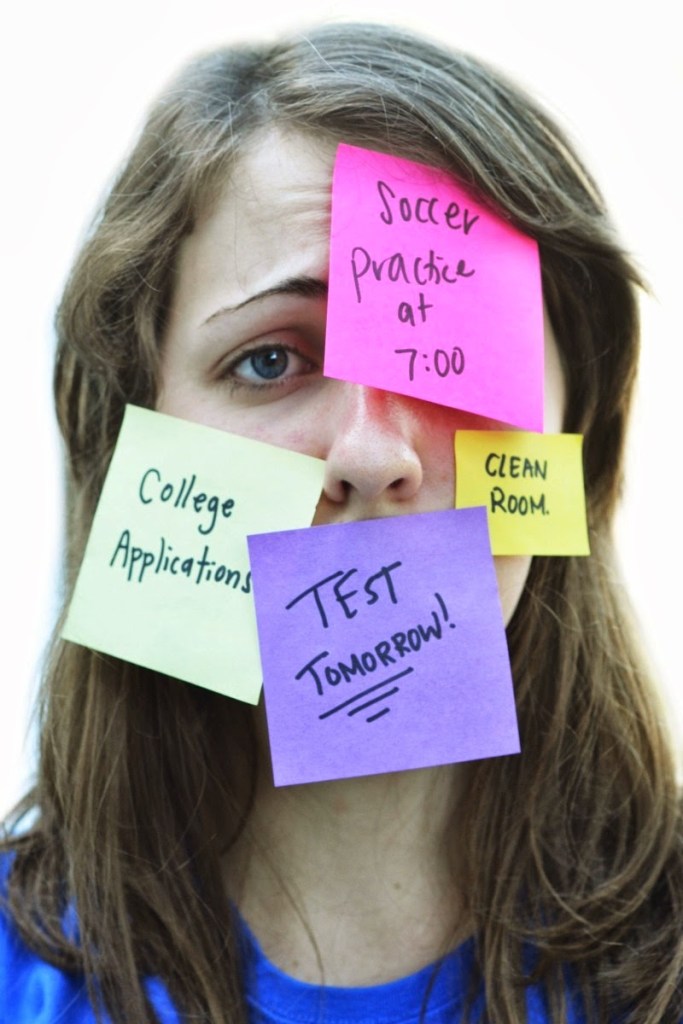

According to the American Social Anthropologist, Allison Davis, the process of socialization may involve, for some individuals, anxiety and distress (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 41). This distress has been referred to as “Socialized Anxiety” (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 41), and it is considered to play a significant role in influencing our behaviour (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 41). Among adolescents, it is widely accepted that “Socialized Anxiety” plays an important role in the process of personality development as well as in allowing the individual to gradually mature (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 41).

For example, an employee might feel the need to work harder due to his anxiety about his work-performance, or, in the case of students, individuals might attend classes more regularly, in order to get better grades, which would allow them to gain entrance into prestigious colleges or universities.

Adolescents, in a similar way, learn more about others’ expectations from them, as well as about their own role and significance in the society, through increased interactions with others. This allows them to work harder and make progress in terms of maturity, which allows them to be approved of by others. It must also be remembered that adolescents tend to believe that others, especially those who belong to their own age-group, evaluate them; this leads to them working more harder, as they seek to maintain their appearances among others (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 41).

The Theories of Eduard Sprang, Leta Stetter Hollingworth, and Lewin Field:

According to Eduard Sprang, adolescence “marks the transition period from childhood to physiological, emotional, and psychological changes” (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 42). This transition, therefore, allows individuals to leave, what has been described as, “a period of crisis and volatility” (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 42), and transform into a “completely changed and transformed person” (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 42), to whom society’s values and the prevalent norms appear acceptable, unlike in the past (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 42).

Leta Stetter, however, appeared to believe that this transform is much more gradual, and that the transition period, from adolescence to adulthood, is not divided into a various phases. This view is in sharp contrast to Eduard Sprang’s view, according to which reaching adulthood was akin to a “rebirth”; this term implies that Sprang’s view involved the spontaneous physiological, psychological and emotional transformation of individuals.

Both theorists, however, appear to have believed that this transition, whether gradual or not, involved many changes (such as those that have been mentioned above), including the change of beliefs and values, which Sprang has referred to as “Dominant Value Section). Dominant Value Section consists of values and perspectives that shape an individuals life, starting from adulthood.

According to Lewin’s Field Theory of Adolescence, membership to a social group is an integral part of adolescence, as teenagers, who are unsure about their roles in the society (due to the gradual transition into adulthood), learn more from the other members of the social group, as well as evaluate their peer’s behaviour; this further reinforces peer-pressure, as well as the compulsion to act in the desired way of one’s peers (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 41). Doing so allows the individual to be approved of by others (Coeur et al., 2012, p. 41).

The “Symbolic Interaction” and the “Social Exchange” Schools of Thought:

According to “Symbolic Interaction”, an individual’s role and significance, in a society, is dependent upon their own interpretation of their own value in the society (Coeur et al., 2012, p.43). Adolescents, in a similar way, learn to develop their own separate identities, their own perspectives on issues, as well as establish their own significance in the society (Coeur et al., 2012, p.43).

According to the school of “Social Exchange”, individuals tend to weigh the potential costs of their actions, as well as its potential benefits, before pursuing a certain course of action (Coeur et al., 2012, p.43). In the case of adolescents, individuals often have to conform to the decisions of their peers (Peer-Pressure) in order to be approved of, by others (Coeur et al., 2012, p.43). This leads to poor decision-making, as the individual refrains from weighing the potential costs and the potential benefits of their actions (Coeur et al., 2012, p.43).

Works Cited

Coeur, T.D., Rawes, C., & Warecki, P. (2012). Challenge and Change: Patterns, trends, and shifts in society. McGraw-Hill Ryerson.

Vartanian, L. R. (2000). REVISITING THE IMAGINARY AUDIENCE AND PERSONAL FABLE CONSTRUCTS OF ADOLESCENT EGOCENTRISM: A CONCEPTUAL REVIEW. Adolescence, 35(140), 639.